The Rise and Fall of a Pirate Empire

Early in 1713, an empire of pirates rose in the Caribbean. Some were in it for the gold and some were in it for the politics, but every pirate was a thorn in the side of England’s navy and yet a hero of her people. But could such a rapacious band of criminals truly be an empire?

I.

THE FIRE-SHIP

A creaking line of Naval ships sat anchored in the port of Nassau. The hulking vessels stood shoulder to shoulder, cannons quietly glinting in the evening light as they stared down the defiant town, forbidding its insurgents to approach. Aboard the flagship of this blockade, in his tricorn hat and pleated officer’s coat, stood Governor Woodes Rogers. His eyes swept the town on the shore. Pirates reveled there, gambling and whoring away money stolen from the crown. Rogers’ eyes narrowed. He was here to exterminate them.

A schooner, its flag the white of surrender, glided slowly from the harbor. The men tensed. What was this? A lone pirate with ill intentions wouldn’t dare approach their whole fleet. Perhaps it was a man willing to speak with them. The schooner floated on.

“Should we signal them to stop?” breathed the first officer.

“No. Gun ports are closed,” Rogers said.

But from the mainmast came a cry — “Fire! The schooner’s on fire!”

Too late, his men scrambled into action. The schooner danced with flame, creeping ever forward toward their line of ships.

“Cut the anchor lines!” bellowed Rogers. Sparks erupted as the schooner’s mast collapsed, raining blazing splinters onto their deck. “Get to cover! Get to cover!”

The gun crews were firing at the waterline, trying to sink the schooner before it reached them. Unidentifiable figures were diving off the schooner as it blazed, swimming to a skiff out of cannon range.

Rogers’ heart stopped. Aboard the flaming schooner, illuminated against the flickering shadows and shining with sweat, shone the resolute face of Charles Vane. The pirate grinned at him insolently and jumped into the inky water. Rogers seethed.

THE BRUTAL NAVY

In the early 18th century, the War of Spanish Succession meant that in England, both the Royal Navy and the merchant ships were perpetually in need of recruits. The harsh conditions and disease associated with sailing were well known, and volunteers to join were especially rare. Even without the severe discipline aboard legal vessels, almost half of the crew aboard a vessel were certain to die from tropical diseases (Woodard 35). Desperate for sailors, merchant captains employed men to convince those who were drunk, ignorant, or desperately poor to join their crews.

The Navy had even fewer recruits than the merchant ships, due to their even lower wages and tight hierarchies. Their predicament demanded the more efficient recruiting approach of naval impressment. Press gangs emerged to terrorize the streets, hunting sailors to bring back to their vessels. The gangs were well-paid for each able-bodied man successfully captured and could legally break into homes to search for men. They could even raid merchant ships to take sailors “who had been at sea for months or years” to be “dragged off their merchant vessels and onto warships before they could set foot on land, catch a glimpse of their families, or collect their pay” (Woodard 37). Sometimes, when the small ships near England’s coast were approached by a press gang’s boat, the sailors on the ships would hide. Then, the gang leaders were known to interrogate the ship’s boys, demand to know where the sailors were concealed and whipping them mercilessly. Because the press gangs were endorsed by the crown, their violent methods were simply condoned.

Onboard the merchant and Navy ships, life was just as grueling. Merchant captains were allowed a slightly lesser degree of discipline than Navy captains were, but that discipline extended nonetheless to excessive beatings. Sailors were regularly known to lose eyes and fingers, and sometimes whole limbs. Oftentimes a sailor’s best protection against violence from their superiors was that their relative health was required to continue working. As frequent as violent discipline was, there was still a tremendous demand for able-bodied sailors.

The Navy may have had legal restrictions on discipline, but once out of the harbor, the autocratic captain had unchecked power over his crew and might flog, underfeed, and work them to death. A slave ship near the end of its journey may have been the worst instance of cruelty, as “when food ran low on slave ships, the captain would throw human cargo overboard” (Woodard 42). Some of this need for discipline arose from the urgency of war, but in the Navy pure bullying for its own sake was unstoppable and unquestioned.

It was taken for granted that the officers and captain were simply better than the impoverished crew, a division fueled immensely by social class. Officers and captains were appointed for their wealth and their family’s societal standing, while the crew were overwhelmingly recruited from the streets. There was little chance of moving up in rank aboard a merchant ship, and no chance at all in the Navy.

This experience drove almost all mutinied pirates to create a ship hierarchy based on meritocracy. Too many experienced and competent sailors were infuriated by their superiors’ bungling of tasks and their sadistic punishments. As men who had served under the merchants’ or navy’s brutal, autocratic system, defecting pirates were eager to escape it. The articles of most pirate ships declare the captain, his officers, and the crew agreed equals. Although the pirates were a heterogeneous group of criminals and the culture of each ship varied, it was uncommon to find a pirate crew that mimicked the Navy’s strict hierarchy.

THE ENTREPRENEUR

The war with Spain generated privateers on both sides, crews who preyed on the enemy’ ships, raided their settlements, and were no different from pirates in the eyes of the opposing navy. However, after the war ended, England no longer condoned attacks on Spain. The Treaty of Utrecht in April of 1713 demanded that English privateers stop attacking Spanish ships and vice versa. Most privateers were reluctant to stop, though, because raiding was profitable, if dangerous. Their fidelity to the laws of their homeland — far across an ocean — easily waned. English privateers continued attacking, but so did the Spanish. The continual assault even in peacetime began to worry Englishmen in the Caribbean.

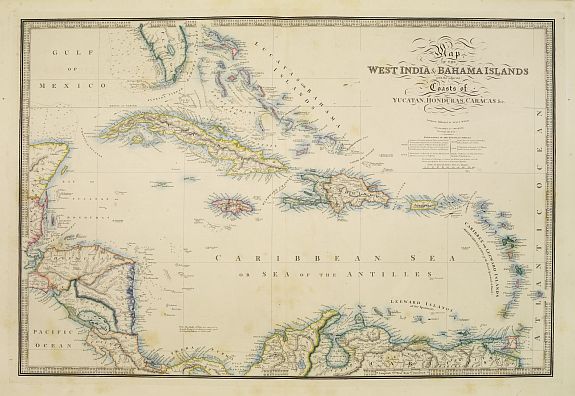

A seasoned Navy man named Benjamin Hornigold was one such Englishman, and together with some fellow sailors, he set up camp in the war-torn town of Nassau, Bahamas, to launch small attacks on Spanish merchant ships. However, without a Letter of Marque, a document granting a privateer to harass and raid enemy ships, a privateer was simply a criminal. Though he still considered himself loyal to the crown, Hornigold’s raids were the actions of a pirate.

THE GOLD

One of the strongest reasons to turn pirate was the enormous trans-Atlantic traffic of Spanish treasure galleons, carrying gold pillaged from the Americas. The allure of easy money drew experienced sailors and land-dwellers both. England was occupied with recovering from the war, for now distracted from the growing pirate problem. Raiders began to disregard the nationality of their victims to prey on any ship they could take. It was the perfect time for criminals to use this opportune chaos.

In 1715 a hurricane dashed open Spain’s annual treasure fleet on the coast of Florida, scattering its unfathomable riches openly over the beaches of Palma de Ayz. Spain formed a salvage camp on the beach to recover its exposed gold, but competitors from all around quickly swept in to scavenge what they could. Of those raiders who arrived too late to scoop the treasure off the beach directly, many turned and robbed it straight from the Spaniards.

As more sailors learned the potential profit and freedom of defecting from the Navy or merchant ships that they served on, more and more crews overtly mutinied or individually ran off to join the rising number of pirates the Caribbean. Having gotten a taste for piracy, many continued to rob ships in the area even after the Spanish gold had disappeared. For some the raids were in the name of their homeland – the English, the Spanish, the Dutch, or the French – but at the heart of it, these men hungered for wealth. Inspired by a mix of loyalty to England and his own desire for gold, Captain Hornigold joined these raiders.

A shrewd orator and a skilled sailor, Hornigold was slightly older than most of the raiders, and in conditions as treacherous as life at sea, age was evidence of durability. His ambition would quickly spur him on to turn this first major success in piracy to a much greater venture: a Caribbean criminal empire.

However, Hornigold was far from the strongest contender for the Spanish treasure. With a massive, well-armed sloop Bathsheba, Captain Henry Jennings made a direct attack on the salvage camps recovering their vulnerable treasure. Coming away with an estimated 87 thousand pounds of stolen Spanish money and goods, Jennings stole an amount more audacious than any other raider at Palma de Ayz. After boldly upstaging both the Spanish and their parasites, Jennings fled to a small but increasingly important town in the Bahamas.

Nassau-town on New Providence Island held only a handful of locals, a spread of farms deeper inland, and a weak-minded governor. Such an unimposing location and influenceable local government must have appealed to Hornigold, because it was at Nassau that he had begun to fortify a scheme for a pirate stronghold.

Hornigold and his equally ambitious co-conspirator, John Cockram had an entrepreneurial plan to capitalize on the growing crop of Caribbean pirates. At Nassau, Hornigold wormed his way into lives of the locals and the pirates that passed through. With his silver tongue and mind for politics, he gradually amassed a following from the pirates that frequented the ungoverned town. When he judged himself strong enough, he made his plan known: he would make piracy a profitable business. He would give these escaped slaves and mutineers a legitimate means to make a living. He would make an empire.

THE SCHEME

Hornigold arranged to buy what the pirates brought back from raids, warehouse and repackage it in Nassau, and ship it to legitimate ports to make a profit. It would be far more effective than attempting to sell obviously stolen goods to a legitimate port, where they could be caught, or in criminal circles, where they would be paid significantly less. Hornigold’s plot let pirates’ merchandise sell for what it would if it were acquired honestly and gave them a better chance at a fortune.

To give them the means to sell off the pirates’ bloody goods, Cockram was sent north to Harbour Island. There he settled and posed as a legitimate merchant. Eventually, Cockram’s business grew believable enough to the locals that he was able to successfully enact Hornigold’s plan. Increasingly perceived as a real trade, they began to profit on the fruits of the pirates’ predatory labor.

Amassing followers and friends, Hornigold sailed to Cuba, where he met Sam Bellamy and his constant partner-in-crime Paulsgrave Williams. Impressed with tales of their exploits, he invited the pair to join his new-formed band of pirates – the self-styled “Flying Gang.” His cohorts included the patriotic Jennings, the terrifying Edward Thatch, the clever Olivier La Buse, and the volatile Charles Vane.

By 1716, the Flying Gang had more than 200 men (Woodard). They grew increasingly successful, running raids in the Bahamas and selling their goods for a tainted fortune through Cockram. Hornigold was pleased; he was well-liked, respected, and powerful – and why shouldn’t he be? Far from the meddling hands of civilization, who branded him a monster, Hornigold lived like a hero.

Hornigold still felt himself separate from the other men but bonded with the enigmatic Edward Thatch over games of strategy and discussions of politics. Thatch was a criminal, like the others, but he was a clever thinker and delightful conversationalist. Recognizing Thatch’s talents, Hornigold made him his first mate on his ship the Ranger.

As with any other organization, however, there was hardly perfect harmony among the Flying Gang. Many men grew tired of Hornigold’s strict leadership and broke off. Vane and Williams were always at odds, Vane’s wild, reckless nature clashing with Williams’ careful, soft-spoken one. Thatch was ever eager to take on bigger enterprises, chase stronger ships, steal better prizes and Hornigold worried he would soon outgrow a position on the Ranger and hunger for his own command. Bellamy stole from Jennings, Hornigold protected Bellamy, and Jennings slandered Hornigold. The infighting continued to cross the already complex loyalties and rivalries among the pirates. The Flying Gang was efficient, rapidly prosperous, and terrifying, but they were falling apart.

As the months wore on, Hornigold began to feel the headache of leadership. Tensions between his allies strained and snapped, pirate betrayed pirate, and for all the wealth they stole, it was inevitably whored and gambled away. Hornigold knew there was no honor among thieves, but he had taken strides to build a civilization. From one perspective, he’d succeeded. They operated like a business, hunting merchants, terrorizing Navies, and getting both more rich and more imposing every day. But Hornigold could not in good conscience call this enterprise a civilization proper. Its members slaughtered one another over a spilled drink, their loyalty was not to a God-appointed king but to the most powerful man of the day, and the entire venture sat atop a sturdy reputation for terrorism.

Hornigold was a practical man, but a moral one. He didn’t enjoy killing, the way Charles Vane seemed to, but neither did he actively abstain from it like Williams did. He knew the level of violence he needed to show to keep merchants surrendering at the sight of a black flag. It was a balance, delicate but essential. There was no more bloodshed than necessary if they kept to the premise that merchants would surrender if promised no harm. But to put them in such consistent fear, the Gang had to continually prove their reputation that they could, if provoked, do great harm.

He would have to contain animals like Vane. He was aggressive and raucous and only encouraged his men to act the same. They didn’t necessarily adhere to the practice of sparing merchant crews who surrendered, and their savagery meddled with the reputation of the whole Gang. If a merchant ship knew they could surrender peacefully, they were far more likely to cooperate. When Vane’s crew raised the black, however, a surrendering merchant crew would be terrorized regardless, which meant they were far less willing to surrender at all. Vane’s unpredictability cost more to the whole Flying Gang than he was worth. To Hornigold, he was a loose end, but if Hornigold had Vane taken care of, he would doubtlessly lose the loyalty of the whole Gang.

A SANE MAN ALONE

One thing haunted Hornigold: as strong as his Flying Gang was, England was always stronger. Sure they were profiting now, but the war with Spain had ended. Any day now, England could decide it was time to clean up the infestation in the Caribbean and sail in with their cannons blazing. The Gang could handle the occasional Navy ship and the meagre defense the Colonies put up, but a true assault on Nassau would be over in a matter of days. Hornigold couldn’t put it out of his mind.

He still felt faithful to England and directed his crew to prey only on the Spanish, Dutch, and French. He may have been a murderer and a thief – he had no illusions about his identity – but he had ideals and loyalty.

Matters grew worse. Hornigold had always refused to fire on English ships, and before when Spanish gold had been plentiful, the others couldn’t care less. Now, however, the other ships were growing ever more careful, and the Flying Gang grew mutinous. They couldn’t afford to spare English ships, whispered their crews. What for, they demanded. Why grow thin for something so insubstantial as an ideal, a loyalty to a King an ocean away?

At last, they turned.

Hornigold’s staunch protection of the English had left him so unpopular that, for all his power, allies dwindled rapidly. The Flying Gang “voted him out of the captaincy [and gave it to] Bellamy” (Golden Age of Piracy). Always a pair, Bellamy and Williams split off, leaving Cuba for the Antilles chain. So too disappeared Vane, Jennings, and LaBuse – and those were only his major players. Crews began to be hard to come by, a sharp change from his previous popularity. Hornigold had known these men weren’t loyal, only hungry, and yet abandonment left bruises on his dignity.

Only one friendly face remained. Thatch, by now having earned the moniker “Blackbeard,” was still on good terms with Hornigold, despite the difference in their methods. To placate Blackbeard’s ambitions, Hornigold had given him a captaincy on another of his ships, the Queen Anne’s Revenge. Though the two still worked in concert, Blackbeard had begun to earn a reputation of his own. When the Flying Gang deposed Hornigold, Blackbeard was away on the Revenge, ignorant of the change (“Golden Age of Piracy”). When Hornigold met him again later in 1717, they spoke very little. Once his closest friend, Blackbeard had turned his back on him.

Hornigold had two identities. He was one of them, certainly, the greatest one of them of all, the founder, the visionary. But at once, he was nothing like them. He’d sailed like them, he’d killed like them, he’d milked civilization for its wealth like them, but at heart, Hornigold knew he was an Englishman. His once-great Flying Gang had left him “only in command of a small crew and a single sloop” (“Golden Age of Piracy”). He knew England was no longer so preoccupied and whether this year or next, would inevitably retake Nassua. Soon, once he could design a plan, it would be time to slip away before his empire fell.

THE PARDON

He didn’t have to wait long. The perfect opportunity arrived in December 1717, when England issued the King’s Pardon. The blanket pardon offered any pirate who took it a return to legal life, and while some staunch pirates refused, a vast majority opted to leave behind the free but dangerous life of piracy for a change at legitimacy and the relative safety of the colonies. They had once been feared, but all men needed to survive even as piracy dwindled. Here they had a way out, a chance to be “rich men in a safe place rather than dead thieves on a long rope” (Black Sails). On hearing of this return to legality, Hornigold sailed on Jamaica to accept the pardon from the local governor, barely a month after it was issued.

Meanwhile at Nassau, a new power took charge. Governor Woodes Rogers had been tasked with retaking the rogue town, and he took the job seriously. English law was rigorously re-imposed and defiant pirates refusing the pardon were executed. Hornigold saw this new governor as an opportunity to reinstate his power, this time in the name of the law. Nassau had a handful of insurgents, steadfast pirates unwilling to relinquish their haven to England’s control.

Those who chose not to take the pardon were damned fools in Hornigold’s eyes. Before, piracy was a one-way road, and no man left except by sword or noose. Now, though, they had a chance to escape this way of live while they still could. What kind of man would turn that down? Only a man as willfully unfettered as Charles Vane. He was far too idealistic, Hornigold scoffed; while most of the men were willing to return to civilization a legal citizen, Vane doggedly refused to take a pardon.

Another man could have escaped unscathed, but Vane had made a reputation for himself as a vicious criminal, a pirate emblem. Rogers put a bounty on him, calling for any man who saw Vane to hand him over for great reward. Of course the men turned – their loyalty was to gold, and England was now the best provider on the island.

On Rogers’ arrival, Hornigold had “organized a formal welcoming party” (Woodard). Rogers increasingly recognized Hornigold as an adamant English loyalist, and took advantage of his willingness to redeem himself to the crown. At Hornigold’s request, Rogers granted him a new ship and a job as a pirate-hunter.

THE HUNTER

Hornigold took to chasing his old allies with as much vigor as when he had been chasing merchant ships, “capturing recalcitrant pirates with the help of his old colleague, John Cockram” (Woodard). He took on the bounties of any fleeing pirate, but Vane was an elusive prize. Hornigold pursued him across the Caribbean. The job was perfect; he chased Vane tirelessly, his previous hatred gratified now that Vane was on the other side of the law. Vane, though, slipped his grasp. He was deposed by his crew, now captained by “Calico” Jack Rackham, and was hanged by authorities at Port Royal.

After leaving the Flying Gang, Bellamy and Williams had taken one of the most well-documented pirate vessels history has seen, the 300-ton, 28-gun slave ship and sloop-of-war, the Whydah (Ferguson). With such a powerful flagship for their gang, Bellamy and Williams were incomparably wealthy in the region. It was unthinkable that their small but potent raiding empire could be broken.

In April 1717, Bellamy and Williams sailed north along the coast toward Massachusetts, where they would separate before re-grouping at Maine's Damariscove Island. Bellamy would sail to Cape Cod in the Whydah, and Williams would go off to visit his home on Block Island. After seeing family - and possibly depositing some of his treasure - Williams sailed to Damariscove Island where he and Bellamy had planned to reconvene. Bellamy, though, couldn’t be found.

Williams waited weeks on the island without rendezvous or word from his partner.

A storm dashed open the Whydah on the shores of Eastham, Cape Cod. Of the massive crew it took to run her, only two men survived the wreck of the Whydah. Bellamy, however, had perished in the storm (Ferguson).

Most men had returned to civilization or died stubbornly. The empire had fallen.

II.

The Republic of Pirates was part-government and part-business venture that formed on New Providence Island, Bahamas, during the most successful era of Caribbean piracy. At its height, the 100 Nassau-town locals were massively outnumbered by the roughly 1,000 pirates that came and went on the island (“A History of Nassau Pirates”). The pirate surge was facilitated ambitiously by Captain Benjamin Hornigold and John Cockram in 1713 in order to sell stolen goods on a large scale, and to form a profitable pirate haven. It lasted only about five years, until the King’s Pardon in 1718.

The Republic of Pirates introduces the dilemma of morality surrounding pirates. How could historical and modern perception romanticize such criminals? Just what makes them criminals and civilization civilized? Could they be considered a civilization proper?

CRIMINALS CREATED BY SOCIETY

There is a conceptual conflict surrounding the idea of civilization. Criminals opportunistically escape civilization, but often turn around to form their own societies. They are detrimental to civilization, but they are politically useful to civilization. They tend to resent civilization, but they are a product of its cruelties and its failures.

Pirates have fled the rule of law, but on escaping must create their own organized systems to profit and survive. Though pirates’ raids were by definition aimed at their own countries or its allies, the politicians at home who villainize them can profit from using such enemies of the law as political tools. Their frequently bitter views of their countries were well-founded. The corruption and lack of meritocracy in the military and the harsh conditions imposed on civilians (such as naval impressment and unchecked exploitation) encouraged a cultural mutiny. As the government increasingly villainized itself to its people, the only things pacifying the populace were brutal local law enforcement and a fearful respect for the clergy. Meanwhile, Europe failed to regulate the Caribbean while it was occupied with war, effectively facilitating its pirate problem.

SOCIETIES CREATED BY CRIMINALS

Can a group designated as criminals be a civilization? To analyze this dilemma, it can be broken into the tasks of identifying the qualities that make a civilization and of defining the distinction between civilization and organized crime.

Is a civilization defined as such because they are genuinely moral? No, because civilizations depend on immoral necessities. A civilization’s enemies are called criminals, but criminality is defined by the powerful. Because of this distinction, there is not necessarily a consistency between what is legal and what is moral.

The word “civilization” itself implies that they are civilized, or humane. However, if a civilization relies on that self-defined morality to feel morally superior, then it’s genuine morality is thrown into question. It seems the truer definition of a civilization is a functional group of symbiotically-interacting people.

The second issue is the criteria on which we separate a criminal empire from a civilization. The band of criminals is produced by civilization’s immoralities, uses civilization’s weaknesses, and is used by civilization’s politicians. It is quite alike civilization: moral and immoral in different ways.

Historically, has there ever been a civilization that has not depended on immoral necessities? Most civilizations have a form of slavery (whether called so or not) that seems to be necessary for efficient economic success. Even those civilizations we now praise as our origins: Egypt, Rome, and early England. Other past civilizations were full of slavery: Spanish encomiendas in the Americas, Russia’s century-long system of serfdom, then the Soviet Union’s Siberian labor camps, and unforgettably the United States’ slavery.

But that lifestyle was not left in the past. Modern day civilizations rely heavily on slave labor, and we are loathe to admit it. Asia’s overpopulation and poverty converge to provide nearly free labor, and the United States takes shameless advantage of their market for dirt-cheap products.

Moral lines between cultures are artificial distinctions that a civilization draws to create personal and political superiority. For example, the Spaniards colonizing Central and South America encountered the natives. Because they were not Catholic and they worshipped "false gods," the Spanish considered them inhuman. They used this cultural distinction to justify a level of sadism that they would find unacceptable toward a fellow Christian. However, for their lack of “correct” religion, the natives were not people in the eyes of the Spanish.

Another example is the early Muslims, who showed no mercy toward captured men of other religions, except for the Christians. Even though Christianity wasn’t considered entirely right in their eyes, Christians were still "men of the book" and of the same essential belief, so they could be spared. The Crusades, too, were horribly violent, but done in the name of morality.

The actions of privateers are deemed good by civilization when they attack the enemies of their homeland. But those same actions are evil or criminal if levelled against people of their own nationality. That sort of hypocrisy demonstrates that our idea of what is morally right is highly flexible depending on the situation. Dividing ourselves into subsections of humanity makes it much easier to justify the atrocities we commit against one another than if we acknowledged that those atrocities are being committed against fellow humans. If we framed the crimes committed against other nations as crimes against the one nation of humanity, those crimes might be felt much more deeply.

MAINTAINING CONTROL

Most civilizations control their citizens with power that is almost entirely implied. Though we may see demonstrations of that power, most of the choices to obey the law is out of respect for the law’s implied power, not because an agent of the law is demonstrating that power.

How can control be exercised with implied power as opposed to demonstrated power? Much of the world relies on implied power, but then it is demonstrated to us when we challenge it. Or, more interestingly, it isn’t, and someone gets away with something that the law — the power — implied it could prevent. When someone encounters a shattered illusion like this, it looks like an opportunity. That was a significant factor that allowed the pirates in the Caribbean to grow so strong, largely with impunity from England.

ROMANTICIZED PIRATES

We desire to emulate their freedom, brotherhood, open rebelliousness, and independently-chosen morality (often just as rigid and valuable as civilized morality but suited to their world).

Stevenson’s Treasure Island had an enormous impact on how the popular image of a pirate. However, the novel was published in 1883, far too late for Stevenson to have first-hand knowledge of the 1700s piracy. Much of his description was either invented or extrapolated from the narrow pool of information available at the time. The images of parrots, buried treasure, and the Black Spot all were Stevenson’s fictions.

Another source for our modern conception of piracy is J.M. Barrie’s Peter Pan. The details of his Captain Hook were mostly fabricated, and contributed to the well-known but mostly false clichés of a captain wearing a decadent red coat, captives “walking the plank,” and every other pirate wearing a hook for a hand.

Most recent and likely most popular, though, is the film “Pirates of the Caribbean,” inspired by Walt Disney’s delightfully detailed theme park ride of the same name. The film series has returned the romanticized image of a pirate to the forefront of pop culture. The phenomenon has spread to a plethora of popular works, from the children’s show “Treasure Planet” to the overblown Hollywood successes of Errol Flynn.

However, the romanticism of piracy is nothing new.

Even as early as 1712, “a playwright named Charles Johnson enjoyed modest success with a work titled The Successful Pirate … based on the exploits of Captain Avery” (Gibson). He is also credited for a widely-known book A General History of the Pyrates, which both Stevenson and Barrie used for reference. The 1726 book is possibly the only primary source on piracy from the era.

Since source material for information on pirates is so scarce, the modern image of a pirate has deviated significantly from its original. Since 1718, they have been cast as heroic rebels, handsome scoundrels, blundering brutes, and everything in between. When pirates walked, though, they were just men: men responding to the brutality of one civilization by creating their own, men fighting to live on their own terms, men on an ocean clashing over loyalty, ideals, and glittering Spanish gold.

Hornigold, for his part, died in 1719 in a raging hurricane near the Bahamas, still hunting down his former allies.

Works Cited

“A History of Nassau Pirates.” Nassau Paradise Island, www.nassauparadiseisland.com/.

Barrie, J. M. Peter and Wendy. Hodder & Stoughton, 1911.

Exquemelin, Alexandre Olivier. The Buccaneers of America. Translated by Alexis Brown, Wilder Publications, 2008. Originally published 1678.

Ferguson, Stuart. “The Who, What, Where of the Whydah: From Slave Ship to Pirate Vessel.” Wall Street Journal, 2007.

Gibson, Tobias. “Pirates of the Caribbean, in Fact and Fiction.” BlindKat Publishers, 1994, pirates.hegewisch.net/.

“Golden Age of Piracy - Notorious Privateers, Buccaneers, Pirates.” History of Humanity - Golden Age of Piracy, www.goldenageofpiracy.org/

Johnson, Charles. A General History of the Pyrates. 4th ed., 1726.

Stevenson, Robert Louis. Treasure Island. Cassell and Company, 1883.

Steinberg, Jonathan E. and Levine, Robert, creators. Black Sails. Film Afrika Worldwide, 2014-2017

Woodard, Colin. The Republic of Pirates. Mariner Books, 2007.

Comments

Post a Comment